History of Lacquer

<Early period>

With the discovery of artifacts decorated using vermilion lacquer dating from the early Jomon period—around 9,000 years ago—at the Kakinoshima archeological site in Hokkaido, the theory that Japan was the world’s source for lacquer craftwork gained credence (unfortunately, these lacquered objects as well as some 60,000 other artifacts were destroyed by fire in 2002). Through the ages, lacquering techniques have been passed down and honed, with durability emphasized at some points in time and the decorative techniques to nurse people’s souls at other points in time.

Bengala (red iron oxide) lacquered earthenware from the Torihama Archeological Site

Collection of the Wakasa History Museum (formerly the Wakasa History and Folklore Museum)

<Asuka period (538-710)>

The Asuka period coincided with the coming of Buddhism to Japan, resulting in the creation of many Buddhist altar pieces, such as the Tamamushi-no-Zushi (Beetle Wing Shrine) of Horyu-ji Temple; on the sides of this shrine are elegantly depicted Shashinshiko pictures, painted using the mitsudae painting technique (referred to as the lacquer painting technique by a number of proponents).

Tamamushi-no-Zushi (Beetle Wing Shrine)

Collection of Horyu-ji Temple

<Nara period (710–794)>

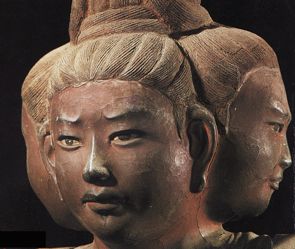

During this period, the Buddhist sculpture masterpiece Statue of Ashura was created using only lacquer and cloth. This statue is world famous as a dry lacquer statue made by wrapping a clay core with layers of hemp, which was then covered with a lacquer base coat called kokuso (a mixture of lacquer, sawdust, and other materials), after which the details were refined, and then a coat of lacquer was added as finishing. The statue’s lonely and painful eyes that stare straight into the observer’s are filled with sincerity, as well as expressing a prayer of pity for the ephemerality of humankind.

Statue of Ashura

Collection of Kōfuku-ji Temple

Collection of Kōfuku-ji Temple

<Heian period (794–1185)>

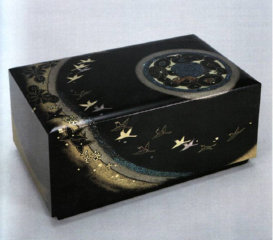

As the era that saw the peak of the Fujiwara clan’s prosperity, many famous lacquer works were crafted during the Heian period. In particular, the Katawaguruma Makie Raden Tebako (Cosmetics Box with Design of Wheels Half-submerged in a Stream) is truly elegant in terms of both its shape and painting design. It provides a glimpse into the lifestyle of Heian nobility.

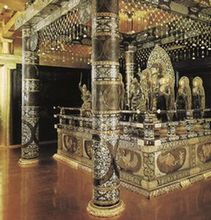

With regard to buildings, the Konjiki-Do (Golden Hall) of Chuson-ji Temple, built by Fujiwara Kiyohira at the end of the Heian period, creates a space featuring lacquer artwork, with the entire hall covered in makie lacquering, mother-of-pearl inlay, and thick gilding. The overwhelming impact of this decoration creates a “land of perfect bliss” that is not of this world. As a building that stands at the pinnacle of lacquer art, the Konjiki-Do’s hall continues to dazzle radiantly today following major restorations during the Showa period (1926–1989). In charge of the Showa period restorations was the late Shogyo Oba (who passed away in 2012), a human national treasure who also happened to be my teacher during my university days. Recalling the restorations, he said, “It was a fearsome restoration project we were undertaking,” expressing admiration for the high lacquering skills of the day and awe at the enormous scale of the project.

In addition, Japan’s oldest story, Taketori Monogatari (The Tale of the Bamboo-Cutter, author unknown) contains a section describing the inside of a house richly decorated with makie lacquering, indicating that at that time in history, there already existed a highly elite group of craftsmen involved in lacquer craftwork, a special group of artisans known as urushibe. The explanatory notes to Taketori Monogatari published by Iwanami Bunko suggest that “the author’s ability to ‘create beautiful rooms painted with lacquer, the walls decorated in makie’, creating a gorgeous fantasy at will, is surely because the author himself was someone with connections to the samurai class that was involved in lacquer work,” inferring that the author was perhaps descended from the nuribe. This is a profoundly interesting inference, and if true, we who are involved in the lacquer craft can be proud to have such a wonderful person of letters among our predecessors.

With regard to buildings, the Konjiki-Do (Golden Hall) of Chuson-ji Temple, built by Fujiwara Kiyohira at the end of the Heian period, creates a space featuring lacquer artwork, with the entire hall covered in makie lacquering, mother-of-pearl inlay, and thick gilding. The overwhelming impact of this decoration creates a “land of perfect bliss” that is not of this world. As a building that stands at the pinnacle of lacquer art, the Konjiki-Do’s hall continues to dazzle radiantly today following major restorations during the Showa period (1926–1989). In charge of the Showa period restorations was the late Shogyo Oba (who passed away in 2012), a human national treasure who also happened to be my teacher during my university days. Recalling the restorations, he said, “It was a fearsome restoration project we were undertaking,” expressing admiration for the high lacquering skills of the day and awe at the enormous scale of the project.

In addition, Japan’s oldest story, Taketori Monogatari (The Tale of the Bamboo-Cutter, author unknown) contains a section describing the inside of a house richly decorated with makie lacquering, indicating that at that time in history, there already existed a highly elite group of craftsmen involved in lacquer craftwork, a special group of artisans known as urushibe. The explanatory notes to Taketori Monogatari published by Iwanami Bunko suggest that “the author’s ability to ‘create beautiful rooms painted with lacquer, the walls decorated in makie’, creating a gorgeous fantasy at will, is surely because the author himself was someone with connections to the samurai class that was involved in lacquer work,” inferring that the author was perhaps descended from the nuribe. This is a profoundly interesting inference, and if true, we who are involved in the lacquer craft can be proud to have such a wonderful person of letters among our predecessors.

Katawaguruma Makie Raden Tebako (Cosmetics Box with Design of Wheels Half-submerged in a Stream)

Collection of the Tokyo National Museum

Collection of the Tokyo National Museum

<Kamakura period (1185–1333)>

From the Kamakura period through to the Muromachi period, lacquer artists produced a type of lacquerware known as negoro lacquerware, frequently seen in museums today. Monks at the Negoro-ji Temple—the Grand Head Temple of the Shingi Shingon sect in Kishu—used for their everyday utensils items painted with vermilion lacquer and black lacquer. The vermilion lacquer finish on items tended to wear down after many years of use, exposing the second coating of black lacquer underneath. The charm produced over those years is highly treasured at present. It should be noted here that the base coatings on these items were applied so thoroughly that the items never lost their beauty, despite long years of wear and tear.

With regard to makie lacquering, the development of makie gold/silver powder progressed during this period; extremely fine gold and silver powder were created. Virtually all of the lacquer craftwork techniques used today are believed to have been established during the Muromachi period.

With regard to makie lacquering, the development of makie gold/silver powder progressed during this period; extremely fine gold and silver powder were created. Virtually all of the lacquer craftwork techniques used today are believed to have been established during the Muromachi period.

<Muromachi period (1336–1573)>

Representative lacquerware pieces from the end of the Muromachi period include the lacquer-painted mausoleum constructed inside the Kodai-ji Temple in 1606 by Kita-no-Mandokoro, the widow of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, to enshrine Hideyoshi’s spirit. The makie lacquering used to decorate this mausoleum is a unique technique called hiramakie (in contrast to burnished makie, very fine gold/silver powder is used and the lacquer is simply polished), also known as kodai-ji makie. Further, furnishing goods finished with hiramakie were subsequently sold overseas as representative Japanese export products.

<Edo period (1603–1868)>

The Edo period was one of stability in Japanese history, thus fostering various aspects of Japanese culture to blossom. In the field of lacquerware, too, artists such as those in the Rinpa School of painting—inspired by lacquerer and craftsman Hon’ami Koetsu—emerged, producing unique lacquerware for the world to admire. As demonstrated by funabashi makie suzuribako (writing box), the novel shape and design created a work of art that exceeded the sphere of craftwork.

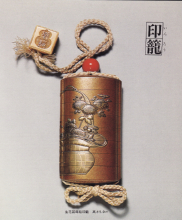

A wonderful lacquered item representative of the Edo period is the “pill box.” Small in size, they were made using the ikkanbari technique, in which numerous layers of Japanese paper are pasted one on top of the other to create the body that is then covered with a fine makie lacquer. These pill boxes were used by not only the samurai class but also Edo’s high-ranking nobility as a status symbol and to carry around medicines.

In addition, lacquer-painted domestic goods came to be produced in regions throughout the country. Such utensils remain indispensable to Japanese culture. From chopsticks and bowls to furniture and architectural interior fixtures, these lacquered objects continue to enrich our everyday lives as aspects of Japan’s unique culture.

A wonderful lacquered item representative of the Edo period is the “pill box.” Small in size, they were made using the ikkanbari technique, in which numerous layers of Japanese paper are pasted one on top of the other to create the body that is then covered with a fine makie lacquer. These pill boxes were used by not only the samurai class but also Edo’s high-ranking nobility as a status symbol and to carry around medicines.

In addition, lacquer-painted domestic goods came to be produced in regions throughout the country. Such utensils remain indispensable to Japanese culture. From chopsticks and bowls to furniture and architectural interior fixtures, these lacquered objects continue to enrich our everyday lives as aspects of Japan’s unique culture.

Pill box

<Meiji period (1868–1912)>

After the age of the samurai drew to a close, Japan opened its doors as a constitutional monarchy. Lacquerware was introduced and presented to the world as a representative Japanese craft at expositions held in various European countries, winning various awards. Subsequently, sophisticated makie techniques gained greater recognition in Western Europe. Representative Meiji artists Zeshin Shibata, Shisui Rokkaku, and Shosai Hakusan established the Nihon Bijutsuin (Japan Art Institute), constructing the foundation for modern-day lacquer craftwork.

<Taisho/Showa periods (1912–1989)>

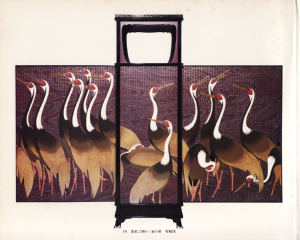

Since the first Imperial Art Exhibition (TEITEN) (now the Japan Fine Arts Exhibition [NITTEN]) held in 1907 as the First Ministry of Education Art Exhibition, lacquerware objects have tread the path toward recognition as works of art. After World War II, the Japan Traditional Art Crafts Exhibition was established separately from the TEITEN. I have been inspired by numerous works by the Showa-period lacquer genius Gonroku Matsuda (a human national treasure), who led the Japan Traditional Art Crafts Exhibition. Looking at the Horai-no-Tana (Cabinet with motif of Horai) that he created together with his apprentice Shogyo Oba (human national treasure) in the midst of World War II (in 1943) easily evokes appreciation of the magnificence of the work as well as the tremendous skill required to create it.

Numerous lacquer panel works, represented by the works of NITTEN’s Setsuro Takahashi (recipient of the Order of Cultural Merit) can surely be positioned as noteworthy lacquerware pieces from the perspective of further expanding lacquerware as art.

<Heisei period (1989–present)>

Today, lacquerware is a well-rounded field composed of works of art centered on NITTEN, traditional craft items, and practical utensils.

When the Nagano Winter Olympics were held in 1998, some 500 gold, silver, and bronze medals made from a mixture of metals and lacquer were placed around the necks of the winners, thereby reaching the far corners of the world. As I have been involved in lacquer work since my youth, I feel fortunate and deeply moved that, as the person who proposed and created such lacquer medals, I have left a mark, albeit a small one, on the history of lacquerware in Japan.

When the Nagano Winter Olympics were held in 1998, some 500 gold, silver, and bronze medals made from a mixture of metals and lacquer were placed around the necks of the winners, thereby reaching the far corners of the world. As I have been involved in lacquer work since my youth, I feel fortunate and deeply moved that, as the person who proposed and created such lacquer medals, I have left a mark, albeit a small one, on the history of lacquerware in Japan.

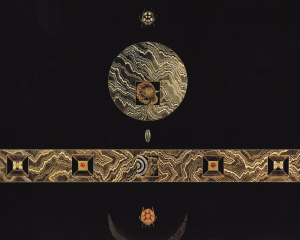

Nagano Winter Olympics lacquered medal

In the 21st century, we face a difficult era for handicrafts amid advances in the high-tech. Nonetheless, I intend to continue taking a step forward. Out of this desire, and through strenuous effort, I was able to complete two watches, by my own hand, for myself—“Sun and Moon.” Oh, I have ended up singing my own praise.

※The photographs used above were taken from the website of the Tokyo National Museum and other facilities with partial permission.